SPOILER ALERT! The plot will be discussed.

Peeping Tom (1960) came out the same year as Psycho, and both films show up in Roger Ebert’s book, The Great Movies. They are both daring artistic psychological works that explore homicidal behavior linked to parent-child dysfunction. They also implicate the audience in wishing to participate in the main character’s perversion through voyeurism. Peeping Tom is even more focused on the connection between filmmaking and watching the private and sometimes gruesome experiences of others.The first images of the film are of a target with arrows shot at a bull’s eye. We immediately have a weapon present and a phallic symbol in the form of the arrow that penetrates and, in this case, is also linked to danger. We then see a human eye (remember Janet Leigh’s dead accusing look at Hitchcock’s audience), which adds to the theme of voyeurism, amplified by the man who is secretly filming a woman in front of a shop window. The sexual aspect is evident when she announces her price, which reveals her to be a prostitute. He follows her to her place, and we see things through the viewfinder of the camera which stands in for the view of the predator (not the first time we see events from the killer’s perspective and certainly not the last in films). We hear the sound of a knife (the same phallic weapon that Norman Bates uses) being unsheathed and then witness the horror of the woman as she is attacked.

The killer is Mark Lewis (Carl Boehm), and he returns to the scene of his crime, filming the aftermath, pretending to be a photojournalist. He records his excursion (he later says he is making a documentary) into this dark realm of fear as the police are there, removing the victim from her home, appropriately covered in a red blanket. He works at a store that contains adult material where he photographs young women in sexy outfits. He repeats what the proprietor has told him that magazines that sell are “those with girls on the front covers, and no front covers on the girls.” So, voyeurism is a business that is profitable, and part of society, although people may not want to acknowledge its presence. Thus, a customer receives his nudie pictures in an envelope marked “educational material.”

When Mark goes into a backroom to do his work one of the models says that her fiancé caught her with another man, and she tells Mark to make sure that her bruises don’t show in the photos. The film shows the seedy side of life and how we try to cover it up, which is what the mainstream movie industry has done in its past. When he takes a while to take her picture, the model, Milly (Pamela Green) asks if he has a girlfriend hidden under the camera’s drape. She is kidding, but she is correct because Mark’s lover is the camera, and his intimacy presents itself in a voyeuristic fashion.

The other model we see only in profile at first. She looks lovely, but then she turns to face Mark and reveals a facial deformity on her right side. She wants the disfigurement to stay hidden, but Mark takes out his own camera and says he wants to shoot her as she is. He does not shrink from the unpleasant side of things. The film may be saying we may kid ourselves that life is not tainted, but that is not reality.

The next scene is at Helen Stephens’s (Anna Massey) apartment where she is celebrating her twenty-first birthday with other tenants. She is attractive and one would think innocent, although her blind mother (Maxine Audley) grunts when a guest expresses a compliment about Helen. Those present see Mark peering in from outside a window. He looks like, well, a Peeping Tom. The lattice work of the window looks like a viewfinder, adding to the connection between film, Mark, and us. Mark lives upstairs, and Helen greets him in the hall, inviting in the outsider, but he declines.Later there is a knock at Mark’s door, and he

immediately does what we all do, try to make the place look presentable, not

wanting others to see that we don’t live in a messy home. Only Mark’s dirtiness

includes his tapes of his sordid activities. He’s an extreme extension of

everyday people. Helen is bringing him a piece of cake. He is awkward with

others because of his anti-social personality. He reveals that he has lived in

that building his whole life. He inherited it from his father, so, he is the

landlord, although nobody knows this fact. As the model Milly noted, he is a

puzzle. He seems so shy and gentle on the surface (like Norman Bates, whose

name sounds like “normal”). He asks if the rent is too high and is willing to

lower it. When she says not to tell the others that he is willing to lower the

cost, she says the renters will give him no “peace.” He repeats the word, as if

not knowing what it means, implying he has had none.

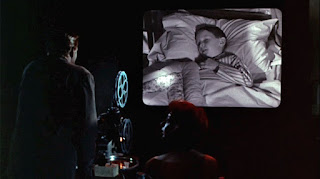

He almost shows her what he was looking at, the removal of the girl he murdered, but he decides not to be that open with her. He instead displays a film of himself as a child, which his father, a scientist, took. The implication is that his father was the influence on Mark’s interest in photography, which is confirmed when there is a scene of his father giving him a camera, the one he still has. The home movie shows how his father experimented on him to see his reaction to fear. He would shine a bright light into young Mark’s eyes which caused him to cry. He dropped a lizard in his bed to frighten him. He also filmed the child looking at two lovers kissing and embracing in the park. He also documented Mark’s reaction to his dead mother and her burial. Helen is obviously upset by these images. Mark now wants to record Helen as she looks at the home movie. His father taught Mark to live life through observing and recording people in distress, and it’s as if Mark is continuing his parent’s scientific studies. Director Powell’s camera shows Mark looking through the turning reel of the film, stressing how he is tied to seeing life through the camera.

As Helen questions him about what this all means, Mark

strokes the camera, a masturbatory action again linking how he can only get

excited by way of his voyeurism. There is the image of Mark’s young stepmother coming

out of the water on the beach, scantily clad in a two-piece swimsuit. We have

arousal in an inappropriate way displayed here by means of observation. He

calls her the “successor,” as if this woman dethroned the queen in Mark’s life

only six weeks after his mother passed away.

After Helen sees how disturbed Mark is, she tells him

to turn off the camera. She moves him away from the dark room, as if she is

getting him out of his dark state of mind, into the lit outer room, where she

wants to shed light on what she saw. Mark tells her his father was a biologist

and wanted to know how fear registered on the nervous system, especially with

children. We see volumes of his father’s books on the topic. Mark says he had

no privacy since his father was always filming him. Thus, he has no problem

invading the privacy of others based on his upbringing. Mark seems to

rationalize that his father learned from him, and some benefitted from his

father’s work. However, Helen doesn’t buy the excuse.

There is then a quick cut to a film set (called The

Walls are Closing In, a foreshadowing) where Mark works, but the impression

is that we have stepped out of the story and are witnessing the filming of the

movie we are watching. It is a deliberate attempt to link imaginary reel life

with actual reality. There is a discussion of whether a movie is commercial

enough to be made, which fits the making of this controversial work we are

watching. There was a criticism of Powell using himself and his son for the characters

of young Mark and his father given the disturbing material of the story. The

movie takes the joining of fictional and actual characters to a daring level.

Mrs. Stephens is a despondent woman who drinks alcohol

to excess. However, even though she is blind she senses the suspicious nature of

the photographer living upstairs. She says, “I don’t trust a man who walks

quietly,” and that his footsteps are “stealthy.” She does condone Helen visiting

him. Mark gives her a pin and when she moves the placement of where she might

affix the gift, Mark moves his hands to the same places on his upper body. Ebert

says Mark here becomes a camera himself, recording what he sees through his own

lenses. Again, he seems to only exist by way of what he observes. She tells him

she is a librarian working in the children’s section of the library and has had

short stories published. She recently had a book accepted about a magical

camera and wants him to help her add photos as part of her story. He is thrilled

but adds a chilling note that sometimes he photographs some things for no

charge. The contrast of the innocence of children and Mark’s dark side is implied

here.

While shooting on the movie set, an actor must move a

trunk, which is especially heavy. We realize from the deadly encounter with

Mark that Vivian’s body is in the trunk, which is discovered in short order. The

police, who are also investigating the prior murder of the prostitute, notice

the same look of terror on the body of Vivian as they saw on the hooker. As

they interview those involved with the making of the film, Mark photographs the

proceedings. Mark talks with a fellow worker and says that he is filming the

police as part of his “documentary.” The other man jokingly questions whether

they will catch Mark recording them. He answers in the affirmative, but he is

talking about arresting him for the killings. It implies that he feels that he

will be apprehended eventually. When the man asks jokingly if he is crazy, Mark

says, “Yes. Do you think they’ll notice?” He is admitting to his deranged

mental state, but he is cloaking it in a humorous exchange.

Chief Inspector Gregg (Jack Watson) interviews Mark,

who offers his camera as a way, most likely, to show that he is cooperating

with the police as to any filming that may prove useful to the investigation.

But he constantly reaches out for it during the scene, like a man reaching for

his lover, or even a part of himself. Mark photographs the removal of the body

from the rafters. As he leans over, objects fall out of his pocket, but he is not

discovered, at least not yet. All the above takes place on the movie set,

sealing the emotional connection between the fictitious moviemaking and actual events.

The sightless Mrs. Stephens again shows her perceptive

abilities as she can feel Mark looking in on them again through the window. She

jokingly says, “Why don’t we make a present of that window?” When she shakes

his hand she says that he has been running. He says he was hurrying to see

Helen, but we know he was escaping the movie studio. Mrs. Stephens asks Mark

about the dead actress, but he claims he didn’t know her. The look on his face

shows that he registers the mother’s suspicious nature.

On their way to dinner, Helen suggests that Mark

doesn’t need to take his always-present camera with him that night. He is

defensive at first, but admits that he trusts Helen, and they lock it in what

was once Mark’s mother’s room. Mark seems genuinely happy to be with Helen.

But, as they head out, he sees a couple kissing, and he instinctively reaches

for where his camera would be slung over his shoulder, ready to capture the

passion between the man and woman vicariously.

While looking at the film he made of Vivian, Mrs. Stephens

surprises him. This is a fascinating scene. We have a blind woman at home in

the photographer’s dark room. She has heard him every night running his camera.

She can keep him at bay with her pointy cane, a version of his knife-like

tripod. He is on the defensive here at first. She asks what he is looking at

and says he can lie to her, but he perceives her intuition and knows she would know

the truth. Vivian’s projected image is partially on the screen and also on his

back, visually implicating him in her fear. The film ends and he lunges toward

the white film screen, arms raised. It appears as if he has been crucified by

his own obsession. He says that the light ends too quickly, and he needs a new

opportunity. He is talking about what he has filmed but what his words imply is

that he feels compelled to seek another victim. It appears it is going to be

the mother. However, Mark relents. The two continue to speak in a code as if

they are talking about film. But what Mrs. Stephens says is that he needs to

seek help and doesn’t want him to see her daughter until he does. He says he

will never “photograph” Helen, which means he would not harm her. She says they

would move away if he became a threat to Helen. He escorts her back to her place,

and she warns him that he will have to tell someone about his problem, a

confession really, and the implication is that it will either be a psychiatrist

or the police.

Back on the movie set, there is a psychiatrist there

to aid the traumatized lead actress. Taking Mrs. Stephens’ advice, Mark asks

the shrink, who knew about Mark’s father, if he had insight on someone being a “Peeping

Tom.” The technical term is scopophilia according to the psychiatrist. Mark is

hopeful, symbolized by his raising the stage elevator as he talks to the

psychiatrist. When he hears that it would take a few years of continuous

analysis to cure, Mark becomes despondent, as he lowers the lift appropriately.

The Chief Inspector is on the set and the psychiatrist mentions to him that Mark

was asking about voyeurism, which piques the policeman’s interest. The fellow

worker he spoke to before gives Mark a photo of a beautiful woman, which Mark

says gives him “an idea.” He then speaks to the man who employs him to shoot

sexy photographs. The audience may suspect that he may make one of the models

his next victim.

The police are now following Mark as he goes to the store to photograph Millie. Mark realizes he is being tailed and it appears that he films the model, then leaves the store, locking up the place. Meanwhile, Helen seeks out Mark, who is not back yet. She turns on one of his cameras, and we see only her response. Her face goes from being in the light to being hidden in darkness, which reflects what she is witnessing. She gasps and whimpers, seeking escape from the room as she realizes the horror of what she is looking at. Mark shows up and she wants to know if the film she watched was just from his “magic” camera, creating an illusion. But he confesses that he killed the women. He tells her that she should stay in the shadows because if he can’t see her fear, she will be safe. How much his father warped Mark is very evident here.

The store proprietor informs the police that he found Milly’s body. So, Mark is allowing himself to get caught. He is driven to commit his crimes, but he is also a sympathetic character because he realizes his mental illness and wants to end his lethal actions. He reveals to her that his father had the whole house wired for sound. and he plays back his screams that his father recorded. She sees his torment and wants to understand what he actually did. He tells her he let his victims see their fear being recorded in a distorted reflection as the tripod knife penetrated their throats. He acts out but does not consummate the crime with Helen. He records his own fear, as his father once did, as he kills himself with his own weapon. The police burst in right after his suicide as a film reel stops rolling, reflecting the end of the movie.

The film has shown us that we are getting our thrills

by also being Peeping Toms. At the end of the movie, we hear Mark’s father

saying to his young son that there’s nothing to be afraid of. Despite the fact

that we are watching a piece of fiction, our fear is real.