SPOILER ALERT! The plot will be discussed.

The title of the film, A Beautiful Mind (2001),

takes on depth as the story of mathematician John Nash unfolds. His mental

abilities produced Nobel Prize winning insights. But, he also was schizophrenic,

so the same mental powers that engendered brilliant rational breakthroughs also

created damaging hallucinations. He was someone who was searching for insights

in the abstract realm of numbers to be applied to the real world, but he also

many times had no connection with reality.

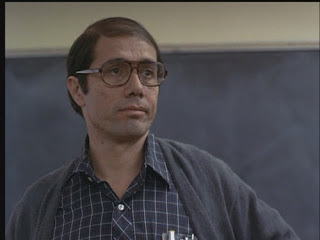

The opening speech from Professor Helinger (Judd

Hirsch) at Princeton University in 1947 to new graduate students places a great

deal of pressure on the entering class. There is a focus on using the science

of mathematics to fight enemies, breaking codes and building the atomic bomb.

Nash sits in the back of the room, his eyes avoiding contact, already

establishing himself as an outsider. Helinger’s outlook may have contributed to

what John Nash (Russell Crowe, excellent here) thought was his purpose and

which fueled his paranoia about foreign adversaries targeting him.

In his room, Nash encounters his supposed

English major British roommate, funny (“Officer, I know who hit me, it was

Johnny Walker) Charles Herman (Paul Bettany), who is suffering from a hangover.

While he cracks jokes, Nash writes mathematical equations on his dorm window, a

sort of metaphor for how his mental powers shed light on his numerical

exploits. In answer to Charles’s questions about him, Nash says he is

“well-balanced” because he has “a chip on both soldiers.” It is comical, but it

also reveals Nash feeling that he must battle adversity. Charles points out that

Nash is better with “integers” than people. Nash adds that he had a teacher who

said he had “two helpings of brain but only half a helping of heart.” This

discussion points to Nash’s lack of emotional connection to others. He admits

that he doesn’t like people and they don’t care for him. He is impatient to

bypass personal relationships so he will not waste time on his quest to map out

“the governing dynamics” of existence and find a “truly original idea” so, as

Charles says, he will “matter.” The two are drinking on a roof, which is

fitting as Nash looks down literally and figuratively on the other students,

calling them, “lesser mortals.”

Hansen challenges Nash to a board game, and he

is astonished that he loses to Hansen. Nash feels his “play was perfect.”

Competition is at the center of Nash’s drive to succeed. It is here that he

starts to investigate “game theory,” which will lead to the idea of those

“governing dynamics” that will be applied to economics and for which Nash will

be most known.

Nash approaches a blonde at a bar and is

unsocial to the point of insensitivity. He says he is not sure what he is

supposed to say so that they can have sexual intercourse, so maybe they should

skip right to having sex. She slaps him and walks out. He must learn to try a

different tactic, as we soon discover.

At present, Nash hasn’t been attending classes,

which he sees as being just derivative, and not aiding invention. He doesn’t

have a topic for his doctoral dissertation, and hasn’t published anything. Helinger

tells him that he can't be recommended for placement in a post-graduate

position. Nash sees recognition and accomplishment as the same thing, showing

his need for validation as the talented outsider.

Nash becomes upset, telling Charles he must follow “their” rules in order to get ahead instead of taking the road less traveled. This idea is symbolized by his pushing his desk away from the window, on which he scribbles his equations, where the light of inspiration shines upon him. Charles counters that argument by telling Nash he must follow his passion outside the walls of the educational institution, and he pushes the desk through the window, watching it fall to the ground. The act shows the need for Nash to break through traditional restrictions on his “beautiful mind.”

Nash is in the bar again. But now he employs a version of game theory when he tells the other math men that if they avoid making a play for the blonde who is present, then they will not have to compete for her, and the other women there will not consider themselves as second choices. That way, they can all “get laid,” and thus win. He says that economist Adam Smith's idea of everyone doing what’s best for himself will automatically be good for the group is “incomplete.” Crowe does a hand gesture with the fingers of one hand curled up touching his forehead. It seems to signify that he has some idea to communicate, but it also shows his shyness, a way of not looking directly at someone. Nash says that the individual must do what’s good for himself and take into account what’s good for the group. He is devising a plan that allows for participation in a goal-oriented strategy that does not have to produce a loser but instead allows each person in the group to win. He goes back to his desk, restored to its spot near the illuminating window, and he begins writing his equations, revising 150 years of economic theory. Helinger is impressed with Nash’s work and gives him the go-ahead to develop his theories on “governing dynamics.” He chooses his pals, Sol and Bender, to be part of his team.

When we catch up with Nash later he has his

doctorate and has gained that recognition he sought, appearing on the cover of Fortune

magazine. The Pentagon calls him to attempt to decipher code they believe

the Russians are transmitting. After looking at a wall of numbers, the digits

illuminate for Nash, and he says that there are latitudes and longitudes among

the figures that relate to routing places in the United States. When he asks

about what the Russians may be planning, he is basically told to leave as he is

not authorized access to further information. He looks up and he sees a man on

a walkway, but the others there do not acknowledge this person.

While in a car, Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s voice is

heard, the man who promulgated the “red scare,” and paranoia about communism.

The belief that the enemy was among us plays into Nash’s personal feelings of

persecution and the urgency being promulgated that mathematics must be used to

fight political adversaries. Nash now works at the defense labs at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He complains to Sol and Bender that the

Russians have the hydrogen bomb, the Nazis found sanctuary in South America,

and the Chinese are gaining force. But he complains that he is being underused

by being assigned to study stress problems in a dam. He has taken Helinger’s

mission that he first heard as a graduate student very much to heart.

Nash must still teach classes as part of the

deal to keep his research projects going. At the class, he throws the textbook

into the trash, showing his disdain for tradition. He sees the class as a waste

of his time. He puts an equation on the board as a kind of test to weed out who

is worthy of his teaching efforts. In the class is Alicia Larde (Jennifer

Connelly, winning a Best Supporting Actress Oscar for this role). By using her

attractive attributes, she is able to persuade the construction workers outside

to be quiet during the class, winning Nash’s admiration for problem solving.

Just as Nash has complained that he isn't getting a chance to show his abilities to fight America’s enemies, the man who Nash called “Big Brother” at the Pentagon observing from above shows up to give Nash a chance at more recognition. He calls himself William Parcher (Ed Harris), and he says he supervised security over J. Robert Oppenheimer’s atomic project. When Parcher brings up how many lives can be lost in the pursuit of weapons, Nash is rather cold, saying progress requires the need for sacrifice. Parcher says Nash’s “lone wolf” life will be advantageous, most likely for performing covert activities. Thus, Parcher’s existence justifies Nash’s anti-social nature and his desire for recognition. As they walk into a “secure” area, Parcher says they know him there, so he doesn’t have to show credentials. Therefore, he does not interact with the guard. The above details become important later.

Parcher takes Nash into what were supposed to be

abandoned warehouses. Inside, he sees many men in white coats operating rows of

computers. Parcher tells Nash he now has top secret clearance, and calls him

the best natural codebreaker around. Parcher’s function then is to bestow the

acknowledgement of Nash’s talents that the mathematician believes he deserves.

Parcher says that the Russians took a portable atomic bomb that the Nazis had

developed, and the locations that Nash identified earlier at the Pentagon are

places the Russians are exploring to explode the bomb. Parcher says that the

Russians are placing coded messages in newspapers and magazines, and that’s why

they need Nash’s help. Parcher makes an interesting observation when he says,

“Man is capable of as much atrocity as he has imagination.” His comment adds

irony to the title of the film by showing the underside of a brilliant

“beautiful mind.” Parcher’s team supposedly puts an implant in Nash’s arm so he

will have access to a drop point where he can deliver his findings.

Alicia comes to his office with what Nash calls

an “elegant” proof of the problem he wrote on the board, but she made

assumptions which didn’t solve the problem. She asks him to dinner, but he says

he usually eats alone, and he says he is like Prometheus with a bird circling

above. His humorous image reveals that he sees himself as a rebel, like the

mythological personage, who gave fire to earthlings. Nash sees himself as a

godlike entity who will endure tribulations to bring mental illumination to

those incapable of such achievement.

Nash takes Alicia to a formal university affair. She is able to navigate his social awkwardness by engaging in his peculiar humor. He draws objects in the night sky by connecting stars with his hand. He sees patterns, maybe where there are none except what we impose on them. The exercise again shows his desire to find form and insights in the universe. However, at the event, he believes men there are observing him, which shows how imagination can warp reality into something ominous. He later drops his sealed classified findings into a lockbox at a gated house by using the changing codes on his implant that are illuminated under a black light. It is done at night and there is a dangerous feel to the place as a car slows down to observe him there.

Nash tells Alicia that his directness has not

been socially successful, so it is an effort for him to adapt to the rules of

society. She encourages him to say what he wants to say. He concedes that even

though he finds her attractive and wishes to have intercourse as soon as

possible with her, he feels he must go through “platonic” romantic rituals to

reach that outcome. He then says he expects a slap across the face, as he

experienced earlier at the bar. Instead, she kisses him passionately, showing

that with her his honesty is rewarded, and how the two are compatible.

Charles reunites with Nash and brings his niece,

Marcee (Vivien Cardone), who Charles says he has taken custody of since the

death of his sister. Charles says he is close by at Harvard. IMDb notes that

when Marcee runs through a field full of birds, they do not scatter, suggesting

that she doesn’t exist. Nash tells Charles about Alicia and wonders how he can

be sure that asking her to marry him is the correct move. Charles says,

“Nothing’s ever for sure, John. That’s the only sure thing I do know.” That unpredictability

comes from a person who supposedly studies literature, an art form, and it

offsets Nash’s longing for mathematical certainty.

Nash meets Alicia at a restaurant and says he

needs “proof” and “verifiable data” that would indicate that they can be in a

long-term relationship. He says this while bending on one knee. It is like a

mathematical marriage proposal. In response, Alicia says she must modify her

notions of romance to accommodate his data-driven inquiry. She asks how big the

universe is, and he says it is infinite. But, he concedes that impression can’t

be proven, so he just believes it. She says it’s the same with love, one can’t

prove it, but somehow just believes it. Alicia is able to show that not all

things, such as emotions and ideas, can be proven, but they still exist within

people.

The two get married, but on his wedding day Nash sees Parcher with a disapproving look, since the lack of attachments to others supposedly justified his service. This image shows the conflict within Nash. When Nash drops a report off, Parcher drives by, tells Nash the spot is compromised, and they are being followed. They speed away as Parcher fires on the approaching vehicle. The terrified Nash sees the enemy vehicle eventually end up in the water. Nash is distant when he goes home to Alicia, and locks the door of his room behind him, as he is now suspicious of everyone, which reinforces his detachment from others. He looks at his students and out through windows and doors as if everyone is a threat. His warped view of reality paints him as a victim of other forces which are trying to destroy him.

Parcher visits Nash in his office, and his

presence is there to prevent Nash from rejecting his immersion into his world

of paranoia. Nash asserts that he has a wife and will soon be a father, and

wants to quit so as to shift his focus to positive things, away from his

preoccupation with fear. But Parcher is here to assert that feeling of dread by

threatening Nash, saying if he doesn’t continue his work, Parcher will not

protect him from the Russians.

There are shadows on the walls of Nash’s house

as he keeps watch through his blinds. They appear to be real, but shadows are

just optical illusions, like Nash’s fears. Alicia begins to realize there is

something wrong with her husband as he acts irrationally, suspicious of why she

turned on the light at night, and then ordering her to leave for her sister’s

place. She looks at the telephone and it seems she is about to seek help for

Nash.

As Nash gives a lecture he sees men entering

from the back of the room that he thinks are enemy agents who are after him. He

says to his students that one can’t assign values to variables, which shows

that Nash can't even find sanctuary among the predictability of mathematics. He

runs out of the lecture hall and he is pursued, but not by enemy agents. Dr.

Rosen (Christopher Plummer) approaches him and says he is a psychiatrist. Nash

punches Rosen and tries to flee. Rosen injects him with a sedative as Nash sees

Charles and his niece observe what transpires.

Nash has been admitted to a psychiatric facility

where he is in restraints. Nash addresses Charles who he sees there, and he

believes that Charles betrayed him by delivering him to the Russians. But,

Rosen says there is no one there. If we haven’t already deduced it, Nash has

hallucinations. Rosen informs Alicia that Nash is schizophrenic, which many

times involves paranoia, and her husband’s belief that he is working to

discover conspiracies is a symptom of his mental disorder. Moreover, Nash’s

occupation allowed these delusions to go on without being discovered. Rosen

gets Alicia to admit she never met Charles, saw a photo of the man, or talked

to him on the telephone. Nash said that Charles was his roommate, but Rosen

discovered that he lived alone at Princeton. Rosen says he must make Nash

distinguish between what is real and what are illusions generated by his

otherwise beautiful mind.

When Alicia gets into Nash’s college office she sees how extreme his activity has been, cutting up magazines and placing pictures and articles all over the walls. Sol and Bender, knowing how offbeat Nash is, gave him a great deal of leeway and did not question his covert activities. Sol followed Nash once to the drop site and now Alicia goes to the estate where Nash was supposed to deliver his findings. The place has been abandoned for some time, with the drop box a broken mailbox and the gate opener busted.

At the hospital, Nash adapts the “facts” as he

sees them to fit his beliefs, as most conspiracy obsessed people do. He says

the Russians can’t kill him because he is too well known, so they are confining

him. Alicia tells her husband that she found out there is no Parcher and no

conspiracy. She shows him all the unopened envelopes he placed in the mailbox.

Of course, he walks out on her because the truth will upend his universe, and

he can’t tolerate that.

He tries cutting out the implant in his arm, but says that it is already gone. Nash starts to get a glimmer of what has been plaguing him. As Rosen prepares Nash for drug therapy, Rosen says how horrible it is to realize that people an individual thought one knew never existed, and that beliefs one held were completely false. It’s as if the “fake news” that one accused others of propagating was real, and one’s own beliefs were the false ones.

Back at Princeton, Alicia tells Sol that the

delusions have passed, but Nash will not show up at Princeton, possibly feeling

shame, where his academic competitor Hansen is now department chairperson. She

feels an obligation to take care of the man she fell in love with, making sure

he takes his medications and encourages him to be active. Sol visits Nash, who

tells him not to sit on Harvey, the imaginary rabbit from the film. Nash has kept

his sense of humor, saying what’s the point of being “nuts” if one can’t have

some fun. But when he hands his indecipherable scribblings to Sol, it is

obvious that Nash isn’t capable of functioning efficiently, as he says, due to

the effects of the medications he is taking. He still feels that his work is

the most important part of his life at this stage. He holds his child while in

a stupor, despondent, devoid of any emotional attachment to his family.

Alicia has her own paranoia concerning what Nash

states, assuming what he says is influenced by his schizophrenia. He tells her

he was talking to the garbage collectors, but she says they don’t pick up trash

at night. Then she sees the men working outside. They both giggle, and she

apologies, probably realizing she too must adjust to what is really happening.

But that light moment is followed by a heartbreaking one as Alicia makes sexual

overtures in bed and he resists. He admits it’s the medication, which can

decrease the libido drastically. She looks devastated, so the implication is

that there has been no intimacy for a long time. She goes into the bathroom and

throws a glass of water at the mirror, shattering both, and screams her

frustration. When Nash takes the shards out to the trash, it is a metaphor for

what is broken in their lives.

Nash secretly stops taking his pills, most

likely so he can provide the intimacy that Alicia wants. But, that brings back

his condition as he is confronted by Parcher who has armed soldiers with him.

He takes Nash to a large shed on Nash’s property that he staffed with personnel

and electronic equipment to pinpoint the location of the nuclear weapon the

Russians want to detonate. Nash tries to deny the existence of what he sees,

but then submits to the fantasy. The film seems to be saying that delusions

which feed our preconceptions are difficult to let go.

Parcher appears and tells Nash that he must get

rid of Alicia because she is a national security risk. After Alicia sees Nash

talking to nobody, Nash then conjures up Charles and his niece, and Charles tells

him to do what Parcher said. Nash is mentally at war with himself, wanting to

believe what he sees but also protective of his family. Then, his mathematical

rationality bursts through with an epiphany that will not allow a delusion to

extinguish. He stops Alicia and says that he realizes that Charles’s supposed

niece, Marcee, never ages; therefore, she can’t be real.

With Rosen present, Nash still sees Charles and

his niece, and Rosen says he must return to the hospital for more treatment.

Nash says the medication stops him from working, taking care of his child, and

responding to his wife. He says he is a problem solver, and he needs time to

figure out the solution. But Rosen points out the dilemma, since Nash’s

condition is not like a mathematical mystery, and Nash’s mind can’t be the tool

to fix things since the defect is in his brain.

Nash does not want to return to the institution,

but fears for how his condition threatens Alicia’s safety. So, he tells her to

go to her mother’s place where the baby is already. But, she refuses to leave

him, and touches him, saying what’s real is in his feelings, not in his mind.

In this way, she expands his sense of reality.

Two months later, Nash visits Hansen at

Princeton University. Hansen says he is an old friend, and he no longer seems

to be a foe. As opposed to feeling that being apart from others allowed him to

excel without distractions, Nash now sees being part of a community will help

him become mentally healthy. He just wants to be able to hang out in the

library. But, he appears outside, fighting his demons, as Parcher resurfaces

and harasses him, while others watch as Nash argues with an illusion.

But, with Alicia supporting his fight to

overcome his symptoms without resorting to extreme medical treatment, Nash goes

back to the college library each day, writing equations as he once did, on the

windowpanes, letting the real and figurative light shine upon him. He now

refuses to speak to his imaginary creations.

Time passes, their son grows up, and there is

now a gray-haired Nash in 1978 still working on equations at the Princeton

University library. He eventually engages with some students and expresses a

desire to teach again. He admits to Hansen that he still sees Parcher, Charles

and Marcee, but since he has ignored them, they don’t intrude anymore. Hansen

says that they still haunt him, but Nash says. “They are my past. Everyone is

haunted by their past.” The problem he must deal with, though, is that Nash’s

past just happens to feel like it has more substance in the present than that

of others.

The next jump is to 1994 and Nash is an elderly

man, but he is back to teaching and working on his math projects. Someone from

the Nobel Prize committee visits him, saying he is being considered for the award

based on his bargaining theories that have numerous economic applications and

eventually even biological evolutionary considerations. Nash realizes that the

visit is to make sure he doesn’t embarrass the prestigious awards ceremony by

acting crazy. He admits to the possibility that he may act out because he still

sees things that aren’t there. He takes newer medications, and says he is on a

sort of mental “diet” where he does not indulge his fantasies. While entering

the faculty dining area for the first time in years the other professors pay

Nash tribute, as he saw they did many years ago for another professor, by

giving him their pens. He has received the recognition he once sought.

The story concludes with Nash’s Nobel Prize speech where he says all of his mental explorations have brought him to the conclusion that, “it is only in the mysterious equations of love that any logic or reasons can be found.” Love, a supposedly irrational area, has provided him the most meaning concerning existence. He directly thanks Alicia for all that he has come to really understand about life as a whole.

The next film is Zorba,

the Greek.