SPOILER ALERT! The plot of the movie will be discussed.

I just stated college when Mike Nichols’ film was released

nationally. The senseless Vietnam War gave the country a feeling of dread. Many

post-secondary school students, like myself, had military draft deferments, but

weren’t sure how long they would last. But, there were wars being fought in the

U. S. ,

too, at the time. There was the fight for civil rights for African Americans.

There were protests at universities against the war in Asia .

There were riots in Chicago

at the Democratic National Convention waged by people who thought the country

was a democracy in name only.

The Graduate

tapped into all of the anti-establishment feelings that were being felt at the

time, but the film itself is surprisingly absent of references to the current

events. There is no mention of the Vietnam War. We do not hear Martin Luther

King’s name mentioned. The University

of California at Berkeley , the epicenter of student unrest at

the time, appears sedate in the overhead shot of the campus. Only actor Norman

Fell’s concern about “outside agitators” reminds us of the tumult that was

going on there. But it is in the non-specific exposure of the affluent society

that created the country’s ills, and the depiction of youth wanting a

meaningful and unique destiny, that makes this movie a timeless story.

Even though this motion picture, with its exclusive zeroing

in on Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman), makes us identify with this young man

in transition, Nichols does not exalt him as a generation’s hero. Does he

petition against fellow youths being sent to war? Is he at rallies protesting

racial discrimination? The answer to these questions is “no.” As was pointed

out in a film class taught by filmmaker Andrew Karasik, he is depicted from the

very first scene as a passive individual being transported through upper

middle-class America .

He arrives home on a jet plane. His luggage, like himself, is moved along on a

conveyor belt. (Although his exiting the terminal through the wrong doors hints

at his future nonconformity). He is given an expensive sports car for travel around

his affluent world as a graduation gift. He is like an early version of Forrest

Gump, where the focus is on the main character as a vehicle to show the

audience the significance of what’s going on around him.

Nichols shows us with biting humor the superficial

world closing in on Benjamin. His graduation party is filled with material

minded people confronting him who only want to tell Ben how his future can be

like their present. There is the famous line of advice about going into

“plastics.” Ben can’t break through to anyone else because no one is listening.

There is no communication in this world. Mr. Robinson doesn’t listen to him

when he asks Ben what he likes to drink, and, at one point, he can’t remember

Ben’s name (an ad lib because actor Murray Hamilton forgot the character’s

name, and Nichols left it in). The shot of Benjamin looking through his

aquarium makes it appear as if his world is claustrophobically enclosed. He

looks like a fish in a tank in one of the last scenes, banging against the

glass at the top, rear part of the church where Elaine is to be married, trying

to escape his prison. There is a plastic (see, everything is made of plastic) frogman

in the aquarium in his room, which foreshadows the scene where his father makes

him wear the underwater gear. All we hear is Ben’s breathing in that scene.

There is no communication again. He is submerged in the

pool, underwater, trapped like a fish in a tank. He literally and figuratively

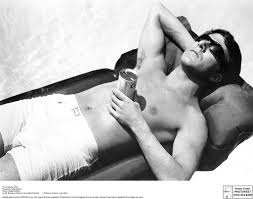

drifts in his circumscribed pool that summer, with no direction. When his

father asks him what was the point of all his education, his reply is “You got

me.” Many of us at that time felt the same way given the type of world the

system produced. Earlier, when asked why he is avoiding the guests at his party,

he says he is worried about his future. He says he wants it to be “different.”

This statement sums up Benjamin’s rebellion, which is a personal, not a

political, one.

There is one person at the party who sees right through to

Benjamin’s angst. The camera provides us with a telling quick look of a woman

observing Benjamin, assessing him. It is Mrs. Robinson (Anne Bancroft), the

wife of Benjamin’s father’s partner. When she asks Ben to drive her home, she

throws the car keys into the aquarium, as if offering him a way out of his

mental prison. However, the way she allows him to be anti-establishment is through a self-serving act of adultery. Why does she try to seduce Benjamin at this particular point? Is

she just manipulative, and sees that he is vulnerable enough so she can use him

to satisfy her wants? Certainly there is an argument to be made for this

viewpoint. She dresses in animal print underwear, emphasizing her predatory nature. Even her enclosed patio is covered in plants, making it appear to be a jungle in which she rules. But, isn’t she finding a kindred soul whose life is as empty as

hers? As opposed to the superficial talk of the friends of Benjamin's parents, she candidly admits to being an alcoholic, a condition that disqualifies her from being a model for the suburban world she inhabits. In a later scene when they are in bed together, she admits to having been

an art major, and now has lost all interest in it. She let her youthful passion

slip away. Possibly she seeks out a younger person to recapture that feeling of

hope for the future. She was a rebel herself, having premarital sex and getting

pregnant with her daughter, Elaine (Katharine Ross). But, she capitulated to

the world of the affluent suburbs, and settled for a loveless marriage of

convenience. However, once she does seduce Benjamin, he is now seen as

corrupted. This corruption is symbolized by Benjamin, an athlete in college,

beginning to smoke once the affair begins, an act which shows his thumbing his nose at the compliance to the rules had had lived by. She, as the mother figure, in an oedipal

manner, has initiated him into defilement. She is already a fallen woman, but

she does not want her daughter to be sullied by being romantic with a man with

whom she had extramarital sex.

It can be argued that Ben’s anemic act of nonconformity is the

unethical decision to have an illicit affair with an older woman. And what kind of rebel winds up with Elaine, who is

the girl his parents wanted him to be with in the first place? But Ben is not

seeking sexual gratification with Mrs. Robinson at first. He says to her,

“Maybe we could do something else together. Mrs. Robinson, would you like to go

to a movie?” He just wants to make a connection with someone who is as

unfulfilled by life as he is. Since she does not want to have a meeting of the

minds, it is appropriate that we hear the song “The Sounds of Silence” in the

background during their lovemaking. To blame Benjamin for breaking up the

Robinson’s marriage, well, it was a hypocrisy to begin with, a “for appearances

only” arrangement. A s far as choosing Elaine, she is, as is Benjamin, as are we all, our parents’

children. Do we become duplicates of them, or are we capable of seeking out

individuality?

When Benjamin finds something he is passionate

about, Elaine, he converts from being passive to being active. He pursues her

at college, runs after the bus that is taking her to her fiancée, and runs to

the church after his car breaks down. The image of Ben heading toward the

camera, however, makes him appear as if he is running in place, getting

nowhere. He is depicted as making an effort, but it is almost Sisyphus-like in

showing how difficult it is to struggle against society’s entrenched

establishment. Nichols depicts him as a Christ figure with hands raised in the

long shot of the back of the church, as if crucified by these perverters of

freedom. It is at this point that Elaine makes her decision to not give in to

her mother’s conformity. In older movies, this type of scene would happen

before the bride and groom are married. This scene takes place after the vows.

Thus, the defiance is emphasized as Elaine tells her mother, “It’s not too late

for me.” Ben literally fights off Mr. Robinson and the others who want to

perpetuate their kind of submission, wielding, blasphemously, from the

churchgoers’ viewpoint, and at the same time appropriately from Ben’s

perspective, a crucifix. Whereas, earlier, doors are used symbolically to show him being closed in or locked out by others, he now closes the church door, locking in his adversaries.

But, at the end, even though Nichols has provided us a

momentary feeling of exalted freedom, he then undercuts that euphoria with the

shots of Benjamin and Elaine, her in her wedding dress, as the two sit at the

back of the getaway bus, a kind of honeymoon conveyance. Earlier, when Ben runs

after Elaine on the way to the zoo, he still winds up on a bus, taking him

away, without him directing its motion. Here again, the two appearing

contemplative, almost sad, not looking at each other, not really knowing each

other, seem to be thinking, “Okay, what do we do now?” They are not driving the

bus, but are being carried to who knows where? Is it possible to direct our own

destiny, or are we just carried along by the currents of life?

Next week’s movie is Network.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please share your thoughts about the movies discussed here.