SPOILER ALERT! The plot will be discussed.

Shattered Glass (2003), based on an article by journalist Buzz

Bissinger, (who wrote Friday Night Lights), deals with what we now call

“fake news.” This story is based on reporter Stephen Glass and his invented

pieces that he wrote for the magazine, The New Republic (which the film

notes “was first published in 1914. It has been a fixture of American political

commentary ever since”). The movie suggests that when an esteemed publication

allows fiction to be published as fact it not only damages the world of

journalism, but also democracy, since accurate information is essential for the

population to make informed decisions regarding their lives. The title of the

movie uses the writer’s name, which implies transparency, and shows how that

pledge of honesty was broken. The movie is subversive, depicting Stephen

(Hayden Christensen) pulling off a deception by presenting the audience with a

cinematic lie. He addresses a journalism class as a celebrity, and, in the end,

we realize we have been conned, just as the real Stephen Glass fooled his

readers.

The film takes place in 1998. Stephen Glass was

the youngest of the staff of twenty-something writers and editors at The New

Republic, which is an indication of how someone with a lack of maturity

found a place there. The opening has Stephen walking around a memorabilia

convention. His narration, ironically, criticizes the self-involved players in

journalism, “the braggarts and jerks” who contrast with those that can write a

“memorable” story that can win a Pulitzer Prize. He mentions that a person

stands out if that individual is “humble,” takes time to remember “birthdays”

and brings a co-worker lunch. But, is Stephen saying that someone is noticed

because he or she is really “self-effacing” and considerate, or can a person

attract the same attention if those qualities are an act? And, is a special

news article memorable because it is genuine, or just a good tale? He says he

is interested in stories about the “quirks” and “flaws” of people, what “moves”

and “scares” them. He is an accurate observer, and records details about human

behavior. It is what a good writer does, whether the work is fact or fiction.

We get a shot of the outside of Highland Park

High School, and then Stephen inside, looking at a display of the magazines he

contributed to followed by his former journalism teacher, Mrs. Duke (Caroline

Goodall), listing his accomplishments. He is charming as he recalls his days as

a student in that very classroom. Mrs. Duke says Stephen is an example of what

happens when “greatness” is demanded of one. It all sounds so inspirational, if

it were only true.

The next scene is at the office of The New Republic in Washington, D. C., and Stephen shows he practices what he preaches. He compliments Gloria (Linda E. Smith), the receptionist, on her necklace and gets small gifts for his colleagues. He even remembers that fellow employee Amy Brand (Melanie Lynskey) likes her diet soda refrigerated, which she mentioned two years ago, and labels a bottle for her with her name on it. Caitlin Avey (Chloe Sevigny) tells him that his most recent piece is good but “a little rough.” Stephen calls it “horrible,” putting his humility on display. He says it’s the worst thing he ever wrote, acting like a devastated child who can’t do anything right after being disciplined by a demanding parent. In a way, Stephen never graduated emotionally from being a child, as his behavior in the film shows. He is overly dramatic, saying he “might have to kill” himself unless he gets help. He gets sympathy and aid by behaving like a hurt boy who needs mothering. He asks Caitlin and Amy if he throws a party, would people play monopoly, which sounds like what kids would do.

Editor Chuck Lane (Peter Sarsgaard), Stephen’s

immediate boss, holds a meeting to check out the status of the stories the

staff members are working on. There is a cut back to the classroom where

Stephen says that it is a “privilege” to be working for the “in-flight magazine

of Air Force One.” He says, again ironically, that it is “a huge

responsibility” to write for such a periodical, and “journalism is about

pursuing the truth.” However, he allows for the devious means of “assuming a

phony identity” to get a story. The film reveals here that the supposedly

innocent appearing Stephen has the ability to be deceptive.

Stephen gives an example of the obstacles to

overcome in getting a story in print by using his article on a conservative

convention for young Republicans, entitled “Spring Breakdown,” as an example.

He again talks about how details make a story convincing, “down to the

mini-bottles in the fridge.” (A similar speech about writing appears in Reservoir

Dogs, analyzed earlier). We then get a dramatization of what was

supposed to have happened when Stephen pretended to be attending the

convention. The young men procure a large woman to come to their room so they

can humiliate her. She runs out of the hotel room, clinging onto her clothes as

the drunken guys jeer at her. Stephen mentions the story to Chuck, noting how

these men were binge drinking, doing drugs, and paying for hookers.

The editor-in-chief, Michael Kelly (Hank Azaria),

questions a fact about the story. Kelly says the hotel where the convention was

located stated it does not furnish the rooms with refrigerators. Stephen again

presents vulnerability to obtain sympathy, stating that he will resign if

necessary if the story will cause damage to the magazine’s reputation. When he

explains that the young men rented a mini-fridge, the discrepancy seems like a

minor flaw in the story. Stephen always says he will check his notes when there

is a question about the reporting, since he later says to the high school

students that in some instances there is a flaw in the fact-checking system,

and “the only source material available are the notes” of the journalist. It is

his way of exploiting the verification process.

Stephen’s immediate response when Kelly has a

problem with the “Spring Breakdown” piece is, “Are you mad at me?” He sounds

like a youngster who is worried that he might have been caught doing something

wrong, and wants the adult’s approval that he is still loved. At the party that

he does have, Stephen says the same thing to Caitlin about her being angry at

him when she disapproves of him for applying to law school. Her response is,

“I’m not your kindergarten teacher,” which shows she is aware of his juvenile

behavior. Apparently, this child-like need for approval comes from not being

able to please his parents unless he becomes a lawyer or a doctor.

At another meeting, Stephen says that following

the infamous Mike Tyson ear-biting incident at a prize fight, he pretended to

be a “behavioral psychologist who specializes in human-on-human biting.” He

told a radio station that he did extensive research on people who “chomp flesh”

when they are under stress. He says that they put him on the air and he took

phone calls for forty-five minutes. His lying to the radio station shows how

capable Stephen is at making up a story. The whole group laughs, and he follows

the response by saying he knows it was “stupid” and “silly,” and he’ll probably

just “kill” the story. He always undercuts his accomplishments with

self-criticism or acts as if whatever he has in the works is “nothing.” This

behavior is consistent with what he said at the beginning about getting

attention by being “humble” in a world of self-promoters. It is part of his ploy

to win over others.

The big boss, Marty Peretz (Ted Kotcheff),

surprises everyone by showing up at the meeting, and Kelly is immediately

tense. He is in conflict with Kelly much of the time on how to run the

publication. Stephen tells the class that Kelly is a great editor, one that has

the “courage” to defend his writers under all circumstances. That quality is

important to someone like Stephen, who we come to realize does not want to be

questioned about his writing. So, it is very upsetting to Stephen, and others,

when Marty fires Kelly, and replaces him with Chuck, who points out to Marty

that he hasn’t built the loyalty of fellow workers the way that Kelly did.

Stephen complains that Chuck gets irritated when others fact-check his own

writing, and stresses that they have to get their facts right, an ironic

statement, as we see, coming from Stephen. As Chuck walks to the Editor’s

office, he gets a silent, unsmiling greeting from the rest of the staff. He

shakes his head slightly, acknowledging to himself that he’s going to have a

difficult time with the transition.

Stephen does tell Chuck that he’ll help him with

moving boxes to his new spot. So, he is already trying to ingratiate himself

with his new boss. Stephen narrates that it began to feel more like a job with

Chuck, which means work was less enjoyable, presumably. He concedes that he

wrote fourteen pieces while Chuck was in his new job, as the titles of the

stories appear. Stephen says his biggest story was about computer hackers. He

says he met Ian Restil (Owen Roth), who Stephen describes as the “biggest

computer geek of all time.” He says that the youth hacked a prominent software

company called Jukt Micronics, inserted pictures of naked women on their

network and listed employee salaries. Restil supposedly left a message that

said, “The Big Bad Bionic Boy has been here, baby!” Stephen says that Jukt

found it cheaper to hire Restil as an IT security worker than to attempt to

prevent his hacks.

Stephen says that Jukt met with Restil at a hotel

where the “National Hackers’ Conference” was going on. We get a dramatization

of Restil demanding a Miata, a trip to Disney World, and subscriptions to

erotic magazines. Stephen gets up and imitates how Restil apparently behaved,

gyrating his hips and shouting, like in Jerry Maguire, “Show me the

money!” The rest of the staff enjoy Stephan telling the story. Stephen says the

teenager was treated like a rock star by the other hackers. Stephen then says

there are several states trying to pass the “Uniform Computer Security Act,”

which would make it unlawful to make deals granting immunity to “hackers and

the companies they’ve torched.” Restil has an agent who has another hacker

client who received a million dollars and “a monster truck.” Again, he says, modestly,

that he may not finish the story, but it is, of course, published under the

title “Hack Heaven.”

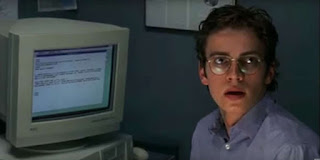

The movie switches to the Forbes Digital office in New York City. Adam Penenberg (Steve Zahn) is called into the office of his boss, Kambiz Foroohar (Cas Anvar), and asked why he didn’t get the Restil story first, since the company deals with tech topics. Adam is surprised by the article and starts to do research. He types in Jukt Micronics in a search engine and comes up with no matches for a supposedly prosperous software company in California. We now get the first evidence that Stephen is fabricating the story. Adam tells Kambiz that there is no listing in the phone book for Jukt Micronics. Also, there is no record of taxes paid by such a firm, and there is no license application for the business. Adam also says his hacker friends never heard of the organization that held the conference, or of Restil or his handle, “The Big Bad Bionic Boy.” Adam found no evidence of the existence of Restil, or Joe Hiert (Terry Simpson), Restil’s agent. Adam is funny when he says the one thing that checks out is that “there does appear to be a state in the Union named Nevada.”

The sad fact is that Stephen is a mentor and

role model for other writers. He tells David Bach (Chad Donella) that he must

verify the facts in his pieces, while Stephen is fabricating his. Amy tries to

imitate Stephen’s humor, which is not her strength. When Caitlin asks if Amy

wants “smoke blown up your ass by a pack of editors,” which is what happens to

Stephen, Amy says, “Yes. Yes it is.” Everyone wants acceptance, but the

question here is whether that attention is earned for genuine reasons.

Things begin to fall apart as Adam from Forbes

leaves a message for Stephen that he wants to do a follow-up piece to “Hacker’s

Heaven,” but can’t locate Restil. Then Chuck asks Stephen for phone numbers

associated with the story, eliciting the usual juvenile “Did I do something

wrong?” and, “Are you mad at me?” from Stephen. Meanwhile, Adam’s co-worker

Andy Fox (Rosario Dawson) becomes curious about the investigation. She tells

Adam she discovered that the “Uniform Computer Security Act,” that Stephen

wrote was under consideration in several states, does not exist. Another writer

adds that the existence of certain individuals mentioned in the story can’t be

verified, nor the National Assembly of Hackers.

Stephen adds typographical errors when he provides the text of emails from sources to add authenticity to his allegations. He tries to dispel suspicions about difficulty contacting his sources by calling them “quirky,” or depicting them as eccentric. He provides the phone number of the chairman of Jukt Micronics, George Sims, who he says, as he does with other contacts, he has spoken to “a million times.” The exaggerated amount also mimics the speech of a child who wants to impress by using a large number. Chuck leaves a voicemail message. When Adam calls and gets the same abrupt instruction to leave a voicemail message, Adam has Andy call at the same time that he does. The fact that one of the calls is always busy confirms his suspicion that it is unlikely that a supposedly large firm gives no other option but to leave a message and has only one telephone line in operation. A person calling himself George Sims returns Chuck’s call and the man is dismissive, saying he will not comment on the article, saying whatever information he gave Glass was supposed to be off the record. He tells Chuck he wants him to “get lost.” Of course the less talk there is with “Sims,” the chances of finding errors in the story are reduced.

Stephen speaks to the high school class, summing

up the numerous fact-checking stages an article must go through that is part of

the magazine’s protocol, and how lawyers and the publisher review the piece for

problems. It is difficult to understand how all these reviews did not catch the

fabrications in Stephen’s stories. The publication’s failure to detect the

deceptions perpetrated by Stephen shows the magazine’s guilt in allowing the

fraud to occur.

At the office, Stephen shows Jukt’s website to Chuck, and it looks like it was thrown together, with only a couple of pages of text, one of which criticizes The New Republic. The hostility is meant to evoke a protective response from Chuck, which is what Stephen experienced with Kelly on the “Spring Breakdown” piece. It does not go as Stephen hoped. Stephen hands Chuck the business card of Joe Hiert, Restil’s agent. It is another bare bones offering, and Chuck comments, “This doesn’t look like a real business card.” Of course, Stephen offers his usual eccentricity explanation, calling Hiert a “clown.”

There is a grueling conference call in Chuck’s

office with Stephen present as Adam says they were either only able to get

voicemail messages of the people noted in the story, or emails were sent back

as undeliverable. Stephen again offers his “million times” hyperbole of the

number of occasions he reached those noted in the piece. On the defensive,

Stephen starts to backpedal, saying he was told that Jukt was a major software

company, but didn’t verify that fact personally. He now says that his story was

misleading if it said that he was in Restil’s home with his agent. Adam’s boss,

Kambiz, says that the Jukt website looks fake, like it “was created to fool

someone.” The camera now stays on Chuck’s face who has been mostly silent, and

he has a look of impatience building as his facial features become more tense. He

now orders Stephen to provide a requested phone number. As he starts to provide

it, Adam points out it does not have the proper area code. Stephen offers that

all of the problems that Adam found indicate that Stephen probably was “duped.”

That would be bad enough, but it would still place the blame of deception

elsewhere.

After the phone meeting, Stephen continues to

push the blame off of himself. He tells Caitlin and others, who see Chuck as

the villain for taking over Kelly’s job, that Chuck didn’t back him up and only

cared about the magazine. But a subsequent phone call between Chuck and Kambiz

shows the opposite. Chuck is concerned about the harm that will be inflicted on

Stephen. Chuck knows he has no control over what Forbes will print, and that is

only fair since The New Republic must take responsibility for its

content. Kambiz at the moment is only going to say that Stephen was the victim

of a hoax, but they must responsibly publish what they found. Kambiz tells

Chuck that they will be asking him for his comments and he wants to know how

much Chuck will stand behind the story. As he holds the bogus-looking business

card in his hand, Chuck says he will have to look into things more. He feels he

must do his own investigation to see what is true and what is false, and,

therefore, how much Stephen is to blame.

Chuck and Stephen go to Bethesda, MD to try to

track down the agent Hiert or at least get some clues as to what really

happened. Stephen tries to make his recollection appear valid by correcting himself

as to where he sat at lunch outside with Restil, his mother (Michelle

Scarabelli), and Hiert, and how they moved because someone smoking bothered

Mrs. Restil. The shot shows the individuals as Stephen acts like he is

recreating the facts, and it seems that what he says actually happened, since

we see them, even though they turn out to be phantoms. Chuck and Stephen go to

the building next door to where supposedly close to two hundred people were in

attendance at the hacker conference in the lobby. The area is obviously too

small for such a gathering, and the man at the desk says that the building is

closed on Sundays, which is when Stephen said the event occurred. Stephen keeps

saying “it’s in my notes,” trying to use that fallback as the journalistic

justification for what he is saying.

Stephen still insists he was there, and Restil and nine others, including Stephen, went to dinner because it was so cramped in the lobby. He says they went across the street to a restaurant, which has a sign that says it was only open until three in the afternoon on Sunday, which means they don’t serve dinner. Stephen says they just made it before the eatery closed. He just keeps improvising to cover himself. He is starting to talk in a rapid, shaky voice now as Chuck chips away at his story. Stephen says Chuck isn’t really having a back-and-forth conversation anymore, which is true. Chuck begins distancing himself from Stephen, ignoring his claim that he is innocent of any wrongdoing. But Stephen persists with his lies, and Chuck says Forbes is going to check out his whole story since the assertions are not holding up. As Stephen continues to say he didn’t do anything wrong, Chuck knows that is not true and yells, “I really wish you’d stop saying that!”

As they ride back, Stephen is so rattled he runs

a stop sign and almost gets into an accident. He finally admits to Chuck that

he wasn’t at the conference. He acts as if he had accounts of the gathering

from others and embellished to have an “eyewitness” feel to the story. Stephen

says he’ll admit that he made it up if it will help Chuck. He is still acting

as if he was fooled. Chuck says, “I just want you to tell me the truth, Steve.

Can you do that?” The question gets to the center of Stephen’s character,

because he isn’t capable of being honest. Lying is his shield against, as he

sees it, being judged unfairly and not getting rewarded as he deserves.

Lewis Estridge (Mark Blum), who works for The

New Republic, falls into the trap that Stephen has created that makes one

feel that they must defend this “confused, distraught kid,” as Lewis calls him.

But Chuck sees Stephen as a devious person who “doctored his notes” and made up

“a bunch of phony quotes” as if they were facts, which Chuck says is offensive.

Lewis offers that Chuck should only suspend Stephen because firing him will

turn the staff against Chuck, and many will quit their jobs so there may be

nobody left to run the magazine. Caitlen joins their conversation, pleads that

Stephen is devastated that he lied to Chuck, and says he is hanging by a

thread, psychologically. Stephen is acting like a scared child afraid of the

punishment his father will dispense on him. Chuck gives in to suspending

Stephen, but for two years. At this point Chuck still sees Stephen as being

deceived by a source, and then he made up stuff to expand on the amount of

information he was fed.

Stephen then goes to the “good cop,” or benign father figure, Kelly, looking for comfort. He acts contrite about blindly trusting his sources and then lying to complete his story. Stephen tries to sell Kelly the idea that Chuck always hated Stephen because Stephen said positive things about Kelly. He says that the real reason Chuck is “punishing” Stephen is because of his “loyalty” to Kelly. Stephen is trying to get Kelly to see Chuck as his enemy and thus come to Stephen’s side of the fight. But Kelly says that Stephen committed “fireable offenses,” and instead of rushing to support him, Kelly wants to know if Stephen “cooked” stories when he worked for Kelly. He specifically asks about “Spring Breakdown,” and Stephen doesn’t answer, so it’s assumed Kelly realizes Stephen’s offenses go way back.

David, Stephen’s fellow journalist, calls Chuck

at home saying that Stephen asked him to drive him to the airport because he

was afraid he couldn’t do it safely. Again, Stephen looks for sympathy from

others by showing what bad shape he is in. David says Stephen said he was going

home for a while. Chuck learns from David that Stephen has a brother at

Stanford University in Palo Alto, CA, which is where Jukt Micronics is supposed

to exist. Chuck now realizes that there was no manipulative source behind

Stephen’s story. He fabricated the whole tale, using his brother to play the

CEO of Jukt, George Sims.

Chuck goes to the office and tells Stephen he

knows he faked everything. Stephen tells Chuck, “You got this totally

backwards.” He is trying to pass off his fabricated world as the real one. The

movie suggests that those who are liars may try to defend themselves by

declaring that their accusers are guilty of the crimes they have committed to

divert attention away from their own misdeeds. But Chuck says he can easily

find the evidence he needs to prove how Stephen engineered his hoax. However,

Stephen will not back away from the fantasy. So, Chuck tells Stephen to leave

without taking anything but his law books, most likely to secure evidence he

needs to show what Stephen has done. When Stephen repeats that he is not a

criminal, Chuck says, “Oh, I heard you.” It’s an acknowledgement of Stephen’s

words but there is no longer a belief in them. Stephen repeats that he is

sorry, like a child who is still learning what and what not to do. But Stephen

is an adult and must take responsibility for his actions, and that is why Chuck

says, “You have to go.”

After Stephen leaves, Chuck takes several issues

of the magazine that contain articles by Stephen off of a display wall. As he

looks at them, Stephen’s voice recites some of the sentences from each in

Chuck’s head. Now that Chuck knows that he is dealing with a liar, he views the

stories from a cynical perspective. He throws the magazines onto the floor with

disgust as the impact of the fraud hits him. Stephen reenters and reinvents his

story, admitting that it was his brother pretending to be George Sims, but he

insists that the man really exists, and Stephen spoke to him “a million times,”

(the exaggeration sounding especially pathetic now). Stephen asserts Sims

stopped talking to him and he was buying time to reconnect with him. Stephen is

delusional to think that, after all his lies, Chuck will believe a new

falsehood. Chuck of course isn’t buying anything Stephen says now and tells him

he is fired (IMDb notes that as Chuck replaces the copies of the magazines on

the wall, there is one issue that has a headline that reads, “Lie About It,” an

appropriate sentence for what is happening in the film). Stephen is now

whimpering, and plays the pity card, asking Chuck to drive him to the airport

because he is afraid of what he might do to himself. Chuck tells him he can sit

and calm himself down, but he declares that he isn’t going anywhere with him.

Stephen can’t believe he isn’t getting the emotional response he seeks and asks

if Chuck heard him. Chuck’s sarcastic comment is, “It’s a hell of a

story.” As Stephen continues to plead for comfort, Chuck puts the last

nail in the professional coffin when he says, “Stop pitching, Steve. It’s

over.” Chuck sees through the fake façade and will not be manipulated any more

by a tale pretending to be true.

As Stephen heads to the conference room for a

staff meeting he assembled, the receptionist, Gloria, makes a good point. She

says that this problem would have been avoided if pictures were taken since one

can’t invent people if they must be photographed. But, that statement shows how

faith in journalism is eroding when one can’t trust that a periodical’s

reporters are trying to be truthful. Chuck thought he was going to face a

hostile group, but he is grateful to find a typed apology to be published for

what happened, signed by all the writers and editors. There are cuts back and

forth to the classroom where the students applaud Stephen, while at the same

time The New Republic staff claps to acknowledge Chuck’s strength of

moral character. That reception is real, but Stephen’s adoration is only in his

head, as he has imagined the school presentation. He is alone in the classroom,

mirroring the emptiness of his world, populated only by fictitious

characters.

The next scene has Chuck and Stephen accompanied

by their lawyers. Chuck reads a list of the titles of articles that Stephen

wrote and the magazine has found to be suspicious. Stephen can object to any

story being considered untruthful. He doesn’t contest any of them.

The notes at the end of the film state that the

magazine apologized for twenty-seven pieces written by Stephen Glass as either

being “partially or entirely invented.” He eventually graduated from law

school. His novel, The Fabulist, was published in 2003. It is “about an

ambitious journalist who invents stories and characters in order to further his

career.” It is ironic that the man who wrote fiction and pretended that the

stories were nonfiction then created a novel that was based on fact. It was not

a commercial success. The movie may be asking what does that say about a

population that prefers to believe that invented stories are real?

The next film is Breathless.

The film brilliantly builds Glass as a brilliant journalist and then unpacks the entire fraud and reveals Glass to be a devious individual who is totally unworthy of sympathy. It is an excellent film.

ReplyDelete